How does solar geoengineering affect precipitation?

Published:

I would like to better understand how solar geoengineering might affect precipitation. Early climate model studies of solar geoengineering (Robock et al. 2008 for example) showed that stratospheric aerosol injection could disrupt the Asian and African summer monsoons. However, the more recent solar geoengineering research shows that the climate outcome of stratospheric aerosol injection very much depends on the location, quantity, and season of injection, and type of reflectant used.

Radiative antidote to CO2

In “Designing a radiative antidote to CO2”, the authors (Jake Seeley, Nick Lutsko, and David Keith) design an idealized reflectant that would perfectly offset the direct radiative effects of CO2. By choosing the spectral bands within which shortwave radiation is attenuated, surface temperature and precipitation are kept to control values after increasing CO2 and reflecting solar radiation in their climate model simulations.

Their main result

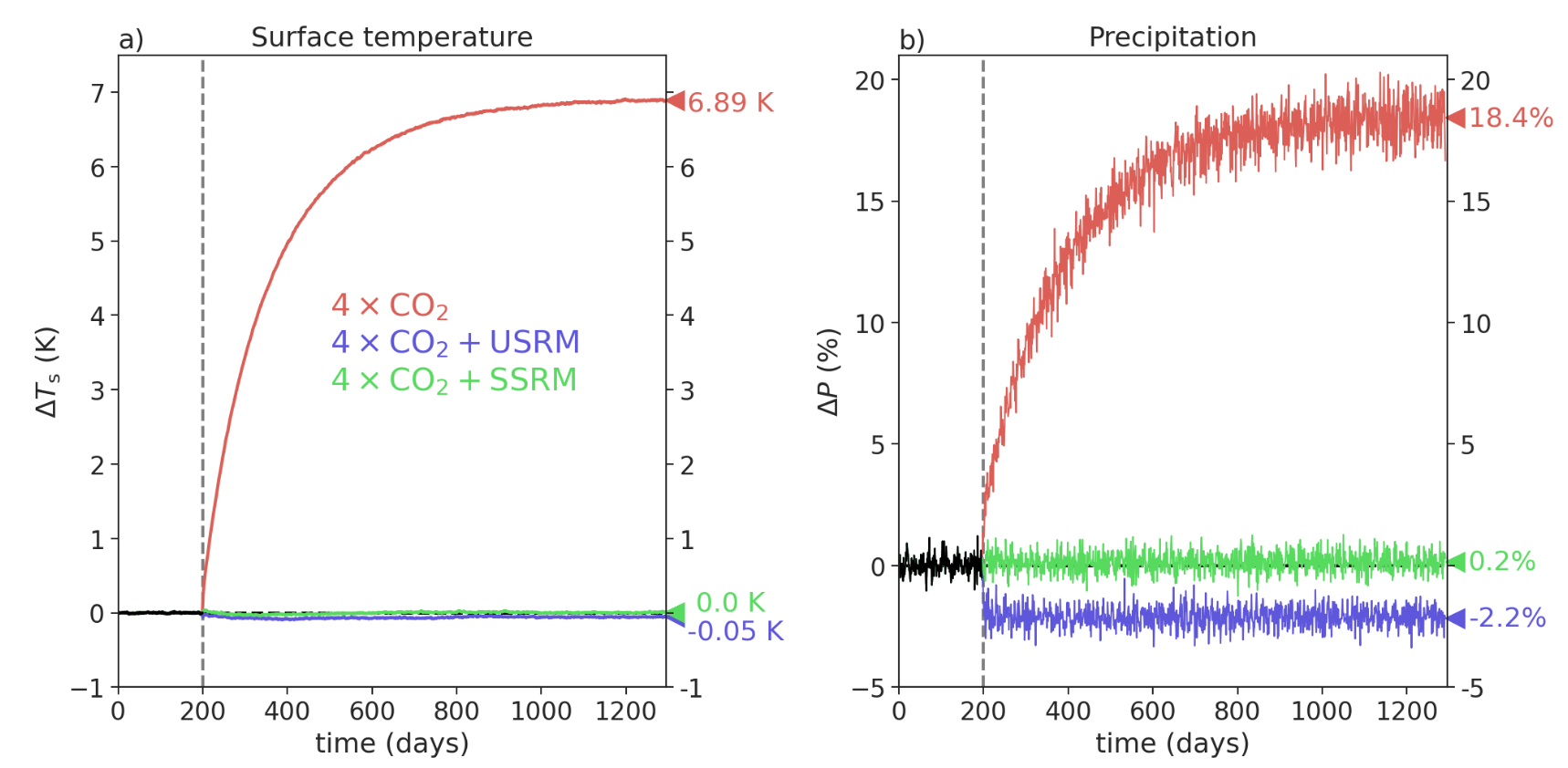

They run radiative-convective simulations with the cloud-resolving model DAM (Romps, 2018). Their figure 4 below shows the surface temperature and precipitation change in their three main experiments. In red (4xCO2), they just quadruple CO2 concentrations, the surface temperature increases by 6.89K and precipitation increases by 18.4%. In blue (4xCO2 + USRM), they quadruple CO2 and apply a spectrally uniform reduction in insolation (like in GeoMIP G1) to keep the surface temperature constant and end up with a 2.2% reduction in precipitation. In green (4xCO2 + SSRM), they quadruple CO2 and spectrally tune the reduction in insolation, such that the surface temperature and precipitation stay constant.

Tropospheric forcing leads to precipitation change

In an atmosphere in radiative-convective equilibrium, radiative cooling is balanced by the latent heat released in precipitating clouds. The change in precipitation ($\Delta P$) scales with the change in tropospheric radiative cooling ($\Delta Q$) by a factor $\alpha_P$ called the “hydrological sensitivity” parameter : $\Delta P = -\alpha_P \Delta Q$.

And, tropospheric radiative cooling can be decomposed into a part directly affected by external perturbation (change in CO2 or insolation, noted $F_a$) and a part that scales linearly with surface temperature change ($\Delta T_s$): $\Delta Q = F_a + \frac{\partial Q}{\partial T_s} \Delta T_s$.

Finally, the surface temperature change scales with the tropopause forcing ($F_t$): $\Delta T_s = \alpha_T F_t$.

In the 4xCO2 case, both the CO2 and surface temperature changes lead to an increase in tropospheric radiative cooling and hence an increase in precipitation. However, in both SRM experiments, the insolation is reduced such that the surface temperature change is zero, therefore only the direct effects of the CO2 and insolation changes affect tropospheric radiative cooling and precipitation.

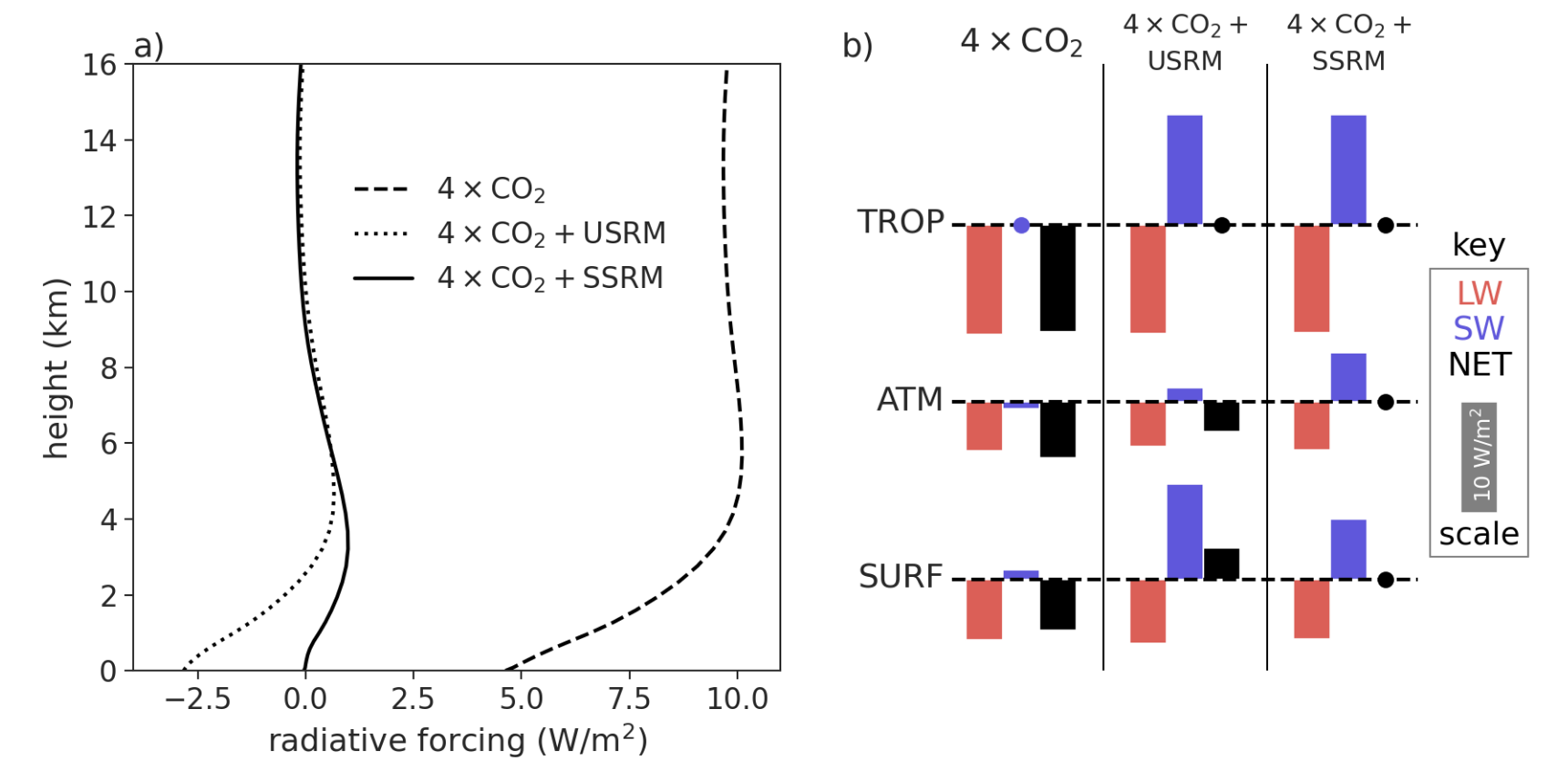

Their figure 2 below shows the vertical profile of radiative forcing on the left and the decomposition into tropopause (TROP), atmospheric (ATM), and surface (SURF) forcings for each case. The tropopause forcing is the sum of the atmospheric and surface forcings, and the net forcing is the sum of the longwave and shortwave forcings. In the 4xCO2 case, the positive longwave forcing from increased CO2 at the tropopause is decomposed into the surface and atmosphere (approximately half each). The spectrally-uniform (USRM) reduction in insolation induces a negative atmospheric forcing that is proportional to the control shortwave atmospheric absorption, which is small. Hence the net atmospheric forcing (CO2 + insolation) is positive, which causes a reduction in precipitation (see equation above, $\Delta P = -\alpha_P \Delta Q$). In the spectrally tuned case (SSRM), the wavelengths are chosen such that the shortwave radiation is partially attenuated in the troposphere, which causes a negative forcing in the atmosphere, which balances the positive longwave forcing from CO2. Hence there is no change in precipitation.

Use this to constrain changes in precipitation in the G1 GeoMIP experiments?

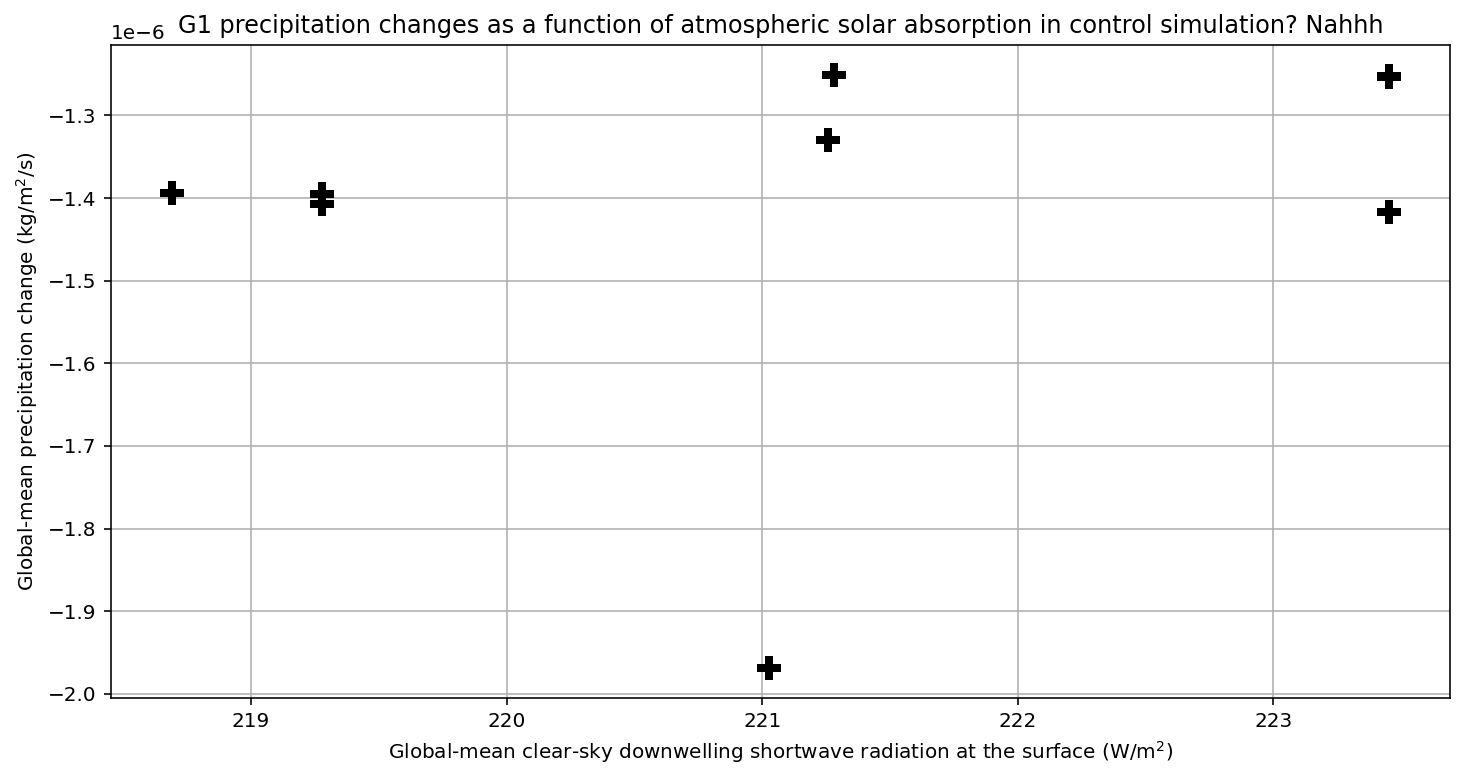

According to this theory, if the control atmosphere is more transparent to shortwave radiation, then the G1 experiment (4xCO2 + spectrally uniform reduction in insolation) should lead to a larger reduction in precipitation. I used some CMIP6 data to see if there is a correlation between the reduction in precipitation between preindustrial and G1 simulations (y-axis) and the shortwave atmospheric absorption in the preindustrial simulations (x-axis). I actually use downwelling shortwave radiation at the surface in clear-sky conditions as the top-of-atmosphere downwelling shortwave radiation should be the same for all models.

However, as shown below, there is no clear correlation between these two variables. Maybe I need more models to have a wider range of precipitation changes, or there is an error in my data processing, or my reasoning is too simplistic.

Implications for real-world solar radiation management deployment

This theory is certainly relevant for the real-world because of the possibility of designing reflectants with the desired spectral attenuations. Moreover, the aerosols that are most commonly discussed do not lead to a spectrally uniform reduction in insolation, hence this theory helps us to understand how the deviation from spectral uniformity affects precipitation.

Leave a Comment