The Early Eocene Equable Climate Problem Re-revisited.

Published:

Models can reproduce Eocene global-mean surface temperature and gradient by having less cloud. But the seasonality of high-latitude land temperature is larger than that suggested by the proxies, and this may be caused by having a smaller cloud radiative forcing.

I released a preprint with Geoff Vallis on understanding the seasonality of high latitude surface temperature, and thought I would share some additional motivation.

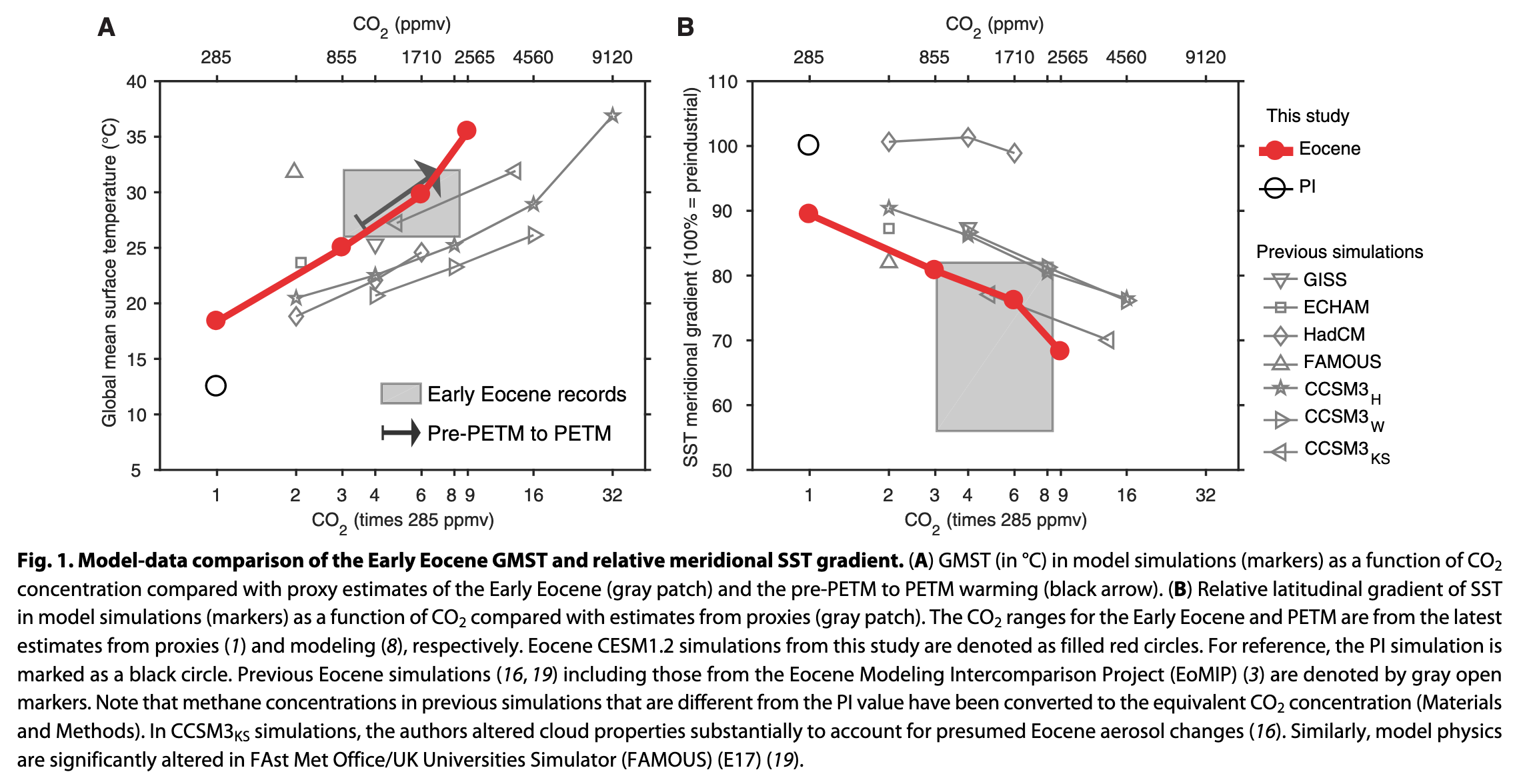

Past warm climates, such as the early Eocene, provide an out-of-sample test for our climate models. What is known as the ‘equable climate problem’ is the realisation that climate models struggle to reproduce the reduced equator-to-pole surface temperature gradient of past warm high-CO2 climates. Proxies indicate that global-mean surface temperature in the early Eocene was 26-32 deg C and the surface temperature gradient was 18-44% smaller than the preindustrial climate (Zhu et al. 2019). While there was large uncertainty about CO2 concentrations in the early Eocene, a recent paper gives a more constrained range: between 1170 ppmv to 2490 ppmv (95% CI), which is between 4 and 9 times preindustrial values (Anagnostou et al. 2020).

Before we had this more constrained CO2 concentration range, Huber and Caballero (2013) showed that a reasonable match between proxies and climate model was achieved by increasing CO2 to high enough levels (4480ppmv). However, those CO2 concentrations are higher than the more recent constraints mentioned above.

Zhu et al. (2019) show that two models manage to have a good temperature match with proxies given the more constrained CO2 concentrations (grey box below). The Kiehl and Shields (2013) model (grey ‘CCSM3_KS’ below) get there by claiming that the Eocene would have much fewer aerosols (warmer conditions make for less biological activity which produces natural aerosols) hence fewer cloud condensation nuclei. Hence they modify the cloud scheme to end up with less cloud, hence a weaker cloud radiative forcing, which gives the warming boost needed. It also leads to additional polar amplification as the increased atmospheric water vapor in the warmer atmosphere gives a greenhouse gas signature to the pattern of warming.

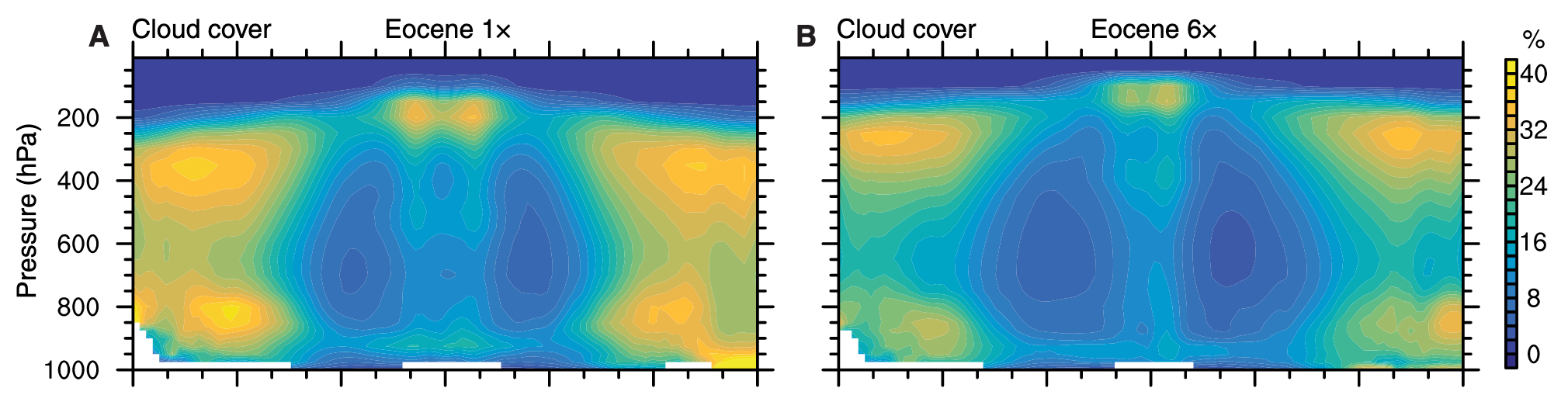

The Zhu et al. 2019 model (red above), on the other hand, is not modified and has a good proxy-model match anyway. The new CAM5 scheme gives a cloud distribution which is in better agreement with recent satellite observations. And, when CO2 concentrations are multiplied by 6, the model has the best fit in terms of CO2, global-mean temperature and gradient (see above, ‘Eocene 6x’) and gives much less cloud (cloud fraction shown below).

Both these models succeed in reproducing the temperature structure of the Eocene with reasonable levels of CO2 by having less cloud, hence a smaller cloud radiative forcing and more warming for a given level of CO2.

The seasonal range in surface temperature provides an additional constraint on the Eocene climate. It is well known that it was above-freezing year-round in the high-latitude continents. Moreover, Eberle et al. (2010) suggest that at several locations around 75 degrees North, the cold month mean temperature was 0-5 degrees C, and the warm month mean temperature was 20-25 degrees C.

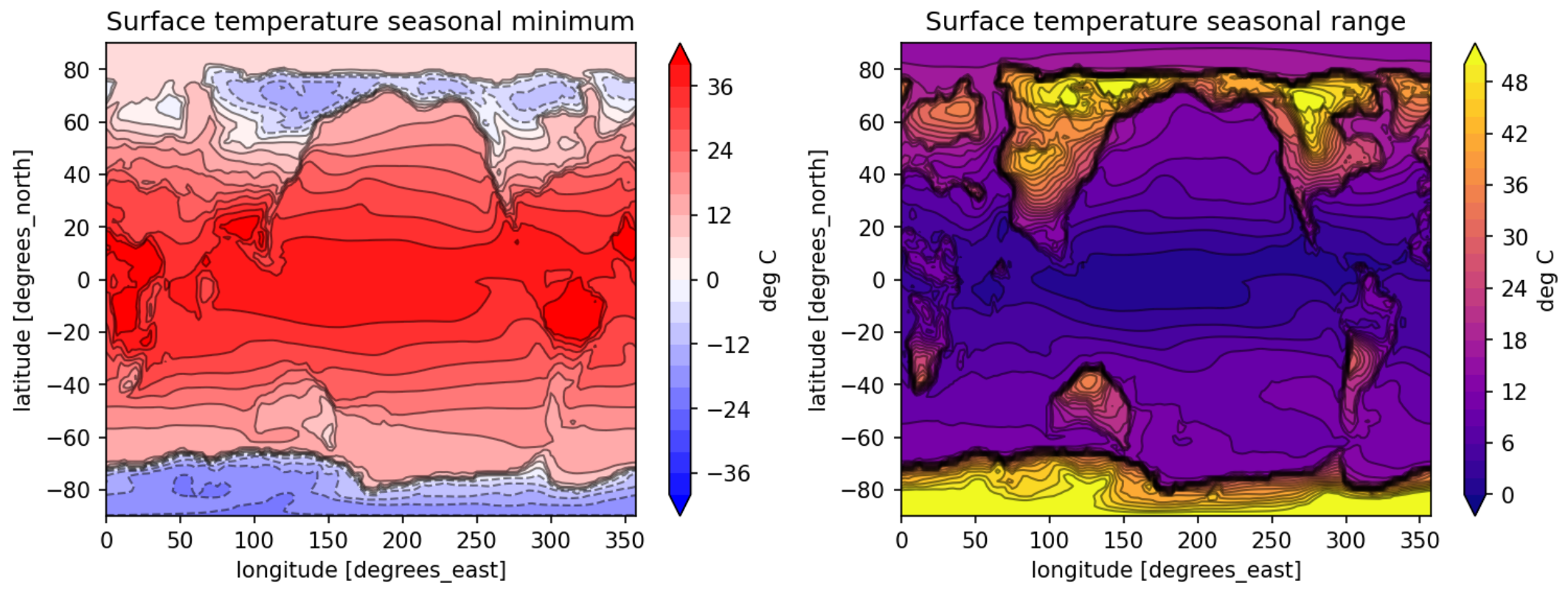

I checked the data from the Zhu et al. 2019 paper (available here) and plotted the cold month mean temperature and seasonal range for the ‘Eocene 6x’ simulation below. The seasonal minimum goes below zero for much of the land poleward of 60 deg N and the seasonal range is 40-50 deg C (about 2x that suggested by Eberle et al. (2010)).

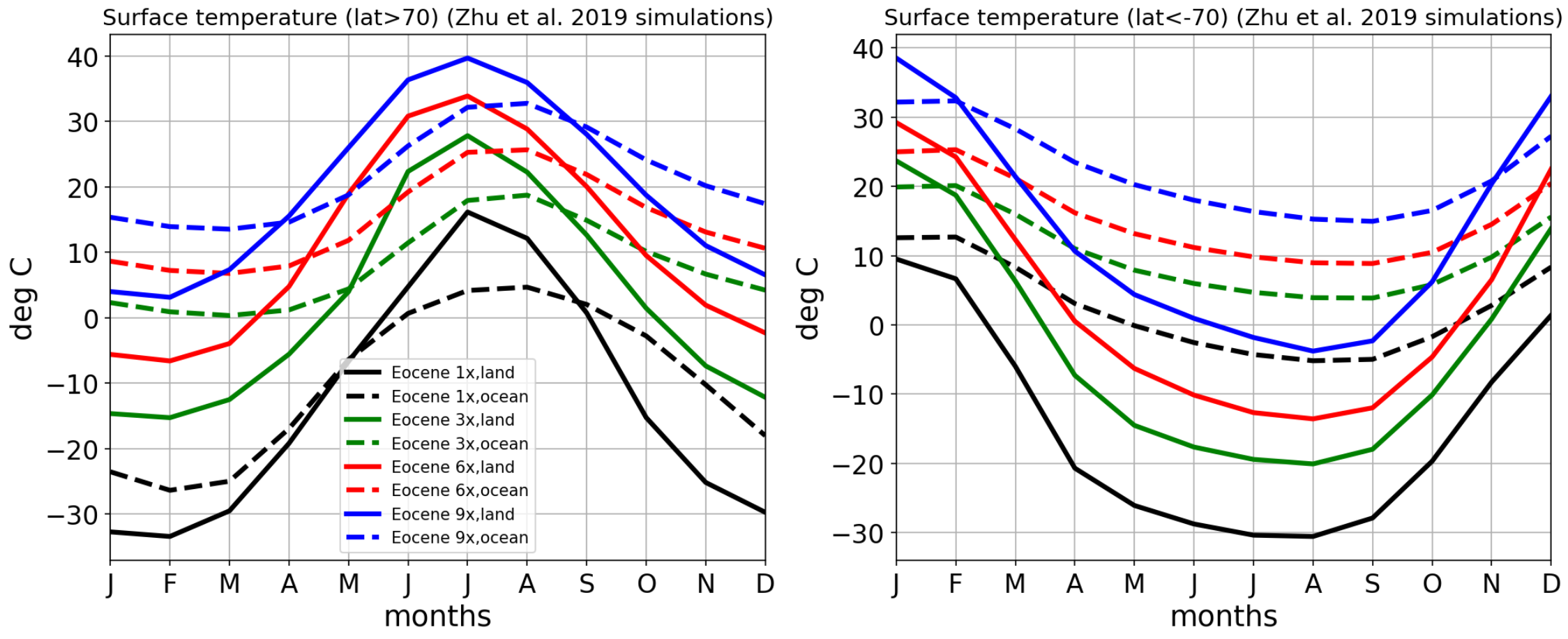

And, below are the high-latitude land/ocean surface temperatures for all simulations. The higher CO2 simulation (‘Eocene 9x’) does have above-freezing temperatures year-round, but the seasonal range is still high, and the annual-global mean temperature is outside the proxy range (first figure).

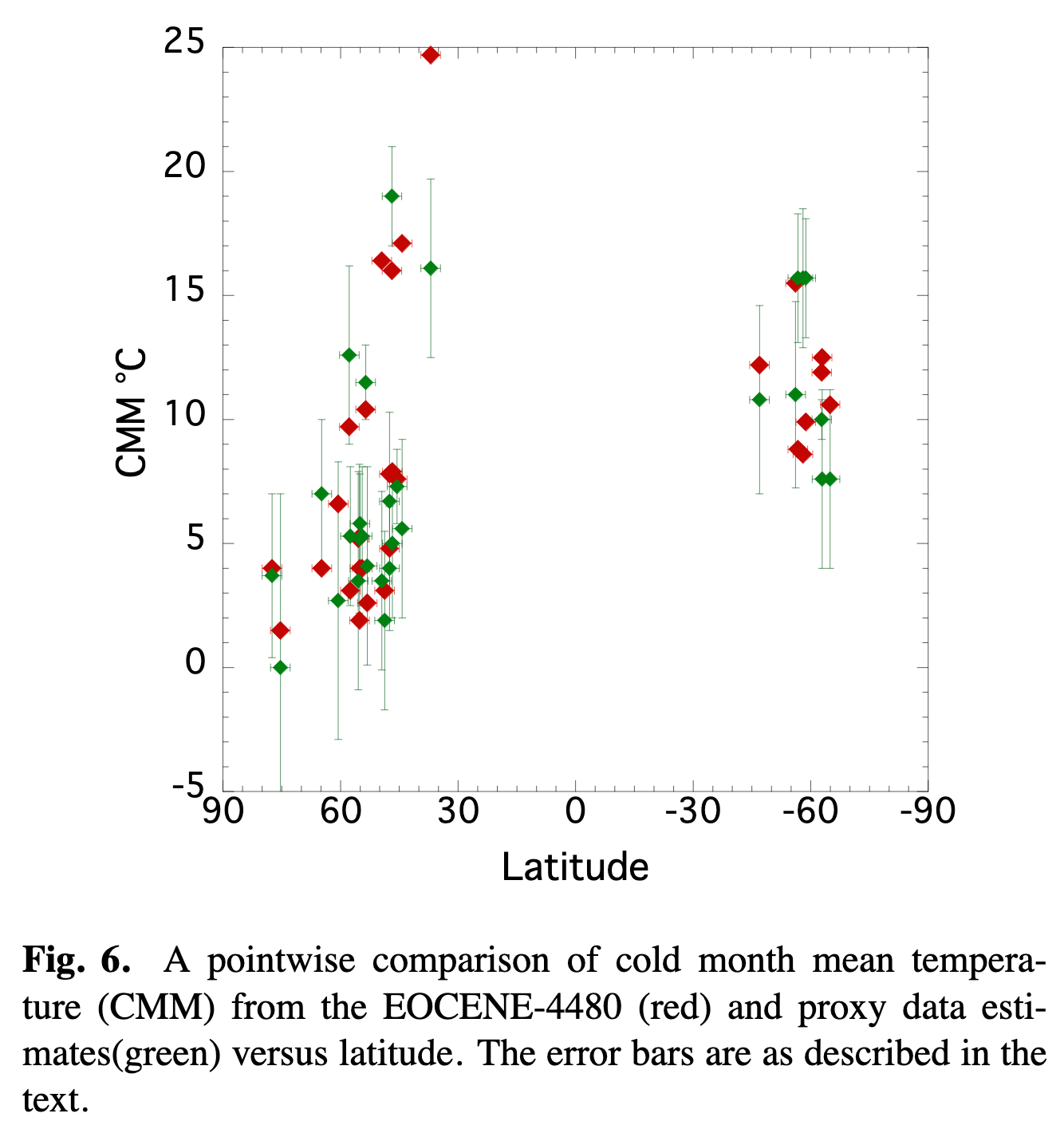

In Huber and Caballero (2013), despite having a high CO2 concentration, there is a good proxy-model match in cold month mean temperatures over land (see below). They argue (in paragraph 4, section 3.1.2) that warm month mean temperatures are much less well-constrained, except at high latitudes where temperatures were in the current climate envelope, although the polar night/day may add an additional layer of complexity.

In our preprint, we show that a high-latitude forcing will reduce the temperature seasonality over land due to its small heat capacity and the nonlinearity of the temperature dependence of surface longwave emission. It is then feasible that the reduction in clouds required to increase the global-mean surface temperature and gradient to match the proxies also increases the high-latitude land temperature seasonality to a value higher than that suggested by the proxies. Hence the reduction in cloud cover might not be the right mechanism to reconcile the Eocene temperature and CO2 concentration.

The explanation could also be simpler: the seasonal proxies are maybe not that well constrained (especially the warm month mean as discussed above), or there is an additional land feature such as different vegetation that would reduce the seasonality over land and not affect the global-mean surface temperature and gradient. Or there actually is an exotic mechanism not present in climate models that gives a simultaneous match in CO2 concentration, global-mean surface temperature, latitudinal gradient, and seasonal range in high-latitude land temperature.

Leave a Comment