(Outreach) What causes the arctic amplification of surface warming?

Published:

A research version of this post is available if you are already familiar with the topic.

The Earth's surface is warming 2-3x faster in the Arctic than the global average. There is still debate on which mechanism is dominant in generating Arctic amplification of surface warming.

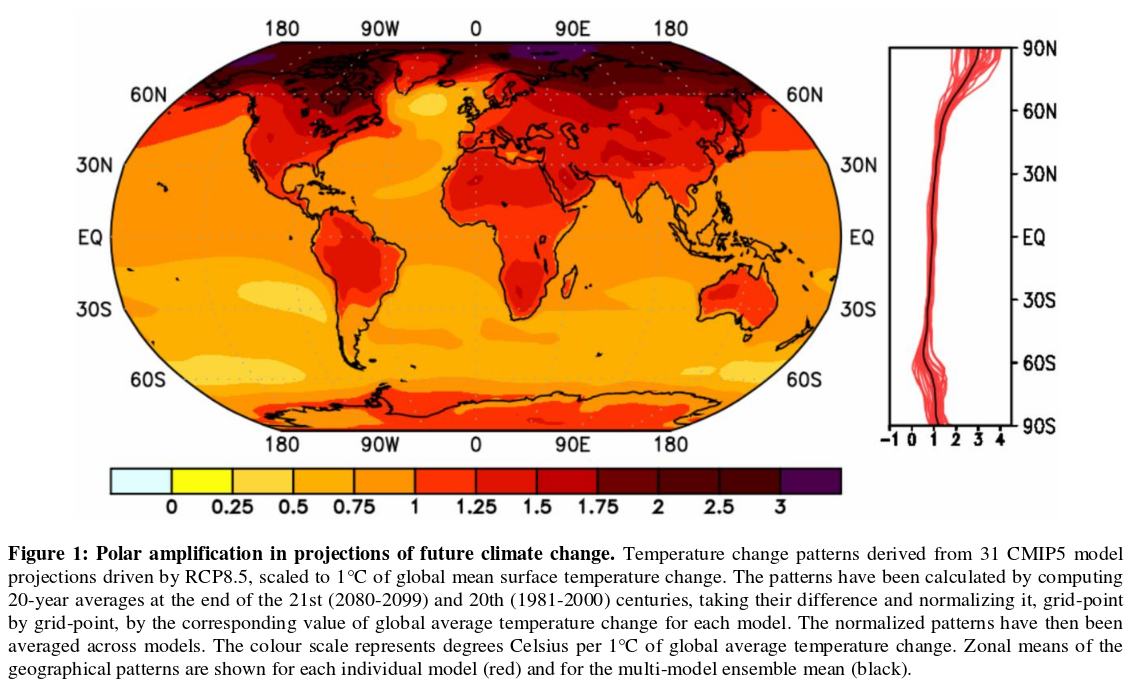

The figure above $($Smith et al. 2018$)$ shows the pattern of surface warming in projections of future climate change. The actual surface temperature change is divided by its global mean to give this pattern. The right-hand panel shows the zonal average of the pattern of warming, each red line corresponds to a different model and their average is shown in black. The Arctic region warms from 2 to 4 times faster than the global mean.

What are the possible reasons for this amplified warming?

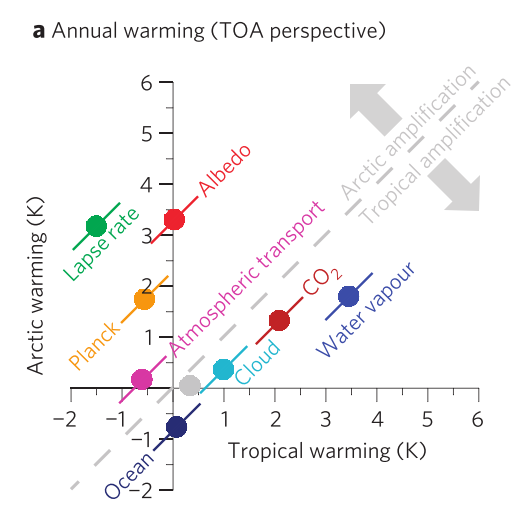

Using radiative kernels, Pithan and Mauritsen 2014 decomposed the pattern of surface warming into contributions from the different climate processes. The figure above shows how much each process contributes to tropical warming $($x-axis$)$ and Arctic warming $($y-axis$)$. The albedo, for example, refers to the positive feedback caused by the melting of sea ice. As a feedback that only affects the high latitudes, it does not contribute to tropical warming $($0 on x-axis$)$ but does contribute to Arctic warming $($around 3.3K on the y-axis$)$. The distance from the one-to-one line $($gray dashed$)$ tells us how much the process contributes to Arctic or tropical amplification.

Idealized climate models

Isaac Held wrote an influential essay on the gap between simulation and understanding in climate modelling, arguing for the importance of model hierarchies. One can think of climate models as being on a spectrum. On one end are the comprehensive models that strive to be as accurate as possible in their description of the climate and their climate change forecasts. This type of model however contains so much detail that it is hard to get an understanding of the physical mechanisms involved. Hence, on the other end of the spectrum are idealized climate models, in which one or more components of the climate are simplified.

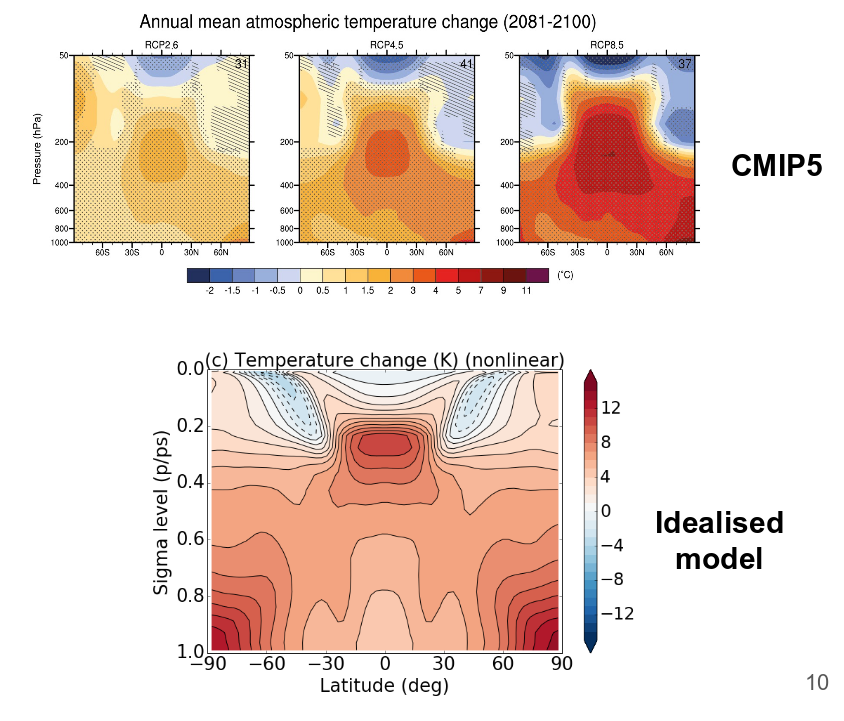

For example, my objective is to understand the structure of warming in the troposphere as greenhouse gases increase. The figure above shows the warming pattern from comprehensive models $($'CMIP5', top$)$ and from a model with a very simple representation of the ocean, no continents, no clouds, no sea ice and a very simple representation of radiative processes $($'Idealised model', bottom$)$. The simple model can approximate the temperature change structure of comprehensive climate models. This suggests that this simple model can be used to study the fundamental physics behind the temperature change structure. We can also use the model hierarchy to test the importance of each mechanism in the temperature change structure. For example, one can remove the sea ice or set its albedo to that of the ocean to test the importance of the sea ice albedo feedback for polar amplification.

Sea ice albedo feedback

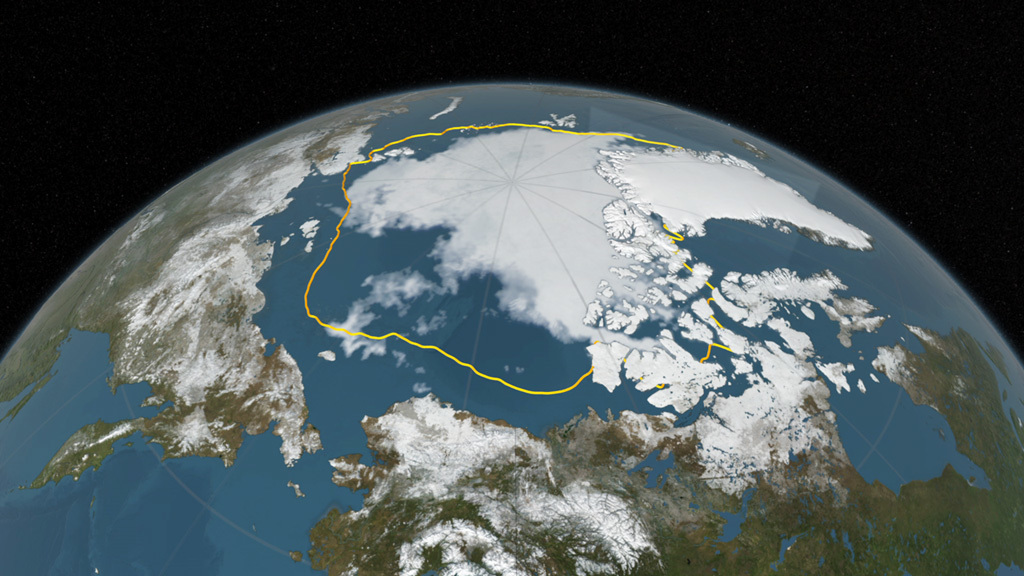

This figure from NASA shows the 2016 Arctic sea ice minimum $($911,000 square miles$)$ and the 1981-2010 average $($gold line$)$. This decrease in sea ice extent means that highly reflective sea ice is replaced by dark ocean waters that absorb sunlight and induces additional local warming.

As can be seen from the Pithan and Mauritsen $($2014$)$ figure, this is one of the dominant mechanisms for Arctic amplification. However, some idealized climate models that keep the surface albedo fixed as the climate warms or have no sea ice at all still have polar amplification. This suggests there are more fundamental mechanisms at play.

Planck feedback

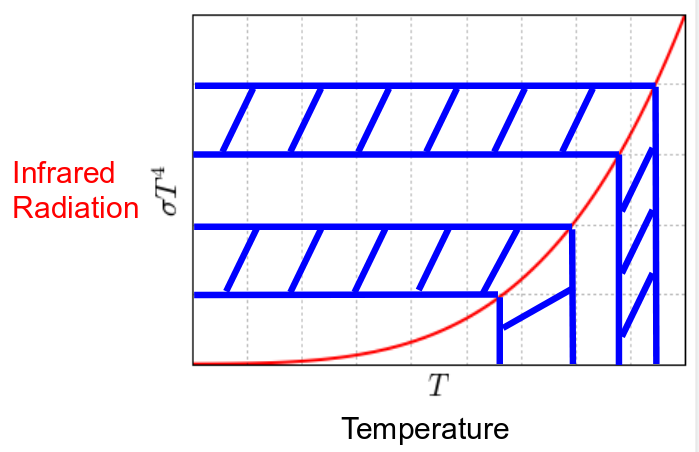

The instantaneous impact of increasing greenhouse gas concentrations is to reduce the outgoing longwave radiation $($OLR$)$ at the top-of-atmosphere $($TOA$)$. Since the global-mean TOA OLR must be equal to the absorbed solar radiation, which we assume does not change, the surface and troposphere must warm to increase the OLR. We artificially separate the vertical structure of warming into a vertically homogeneous part and its deviation. The Planck feedback corresponds to the total increase in OLR per degree of vertically homogeneous warming.

The OLR can be calculated as $OLR=\sigma T_E^4$, where $T_E$ is the temperature of emission. As illustrated in the figure above, $\sigma T^4$ is nonlinear, hence when starting from a cold temperature, a higher increase in temperature is needed to reach the same increase in emitted radiation than when starting from a warm temperature. The high latitudes are colder than the rest of the planet, hence this is thought to be a cause for polar amplification. Moreover, Pithan and Mauritsen's figure shows that the Planck feedback may have an important part to play in Arctic amplification.

My first PhD project consisted in testing how important this mechanism is for polar amplification. We used a very idealized atmospheric model with no continents, no clouds and no sea ice $($Frierson et al. $($2006$)$$)$. This idealized model is able to accurately reproduce the temperature change pattern of comprehensive models. We simply replaced $E=\sigma T^4$ by $E=A + BT$ in the radiation code so that the increase in temperature necessary to increase the OLR is the same for all initial temperatures. This had no effect on the pattern of surface air warming as other factors such as the lapse rate feedback changed to compensate. However, we did find that the $E=\sigma T^4$ nonlinearity affects the vertical structure of warming.

Atmospheric energy transport

Atmospheric energy transport occurs from the tropics to the poles. In the tropics, the absorbed solar radiation $($ASR$)$ exceeds the outgoing longwave radiation $($OLR$)$ $($heat emitted at the top of atmosphere$)$, hence there is excess energy. At the poles, there is less ASR than OLR hence an energy deficit. The role of the atmosphere and ocean is to transport heat from the tropics to the poles. This can be achieved either through advecting warm air parcels from the tropics to the poles or through advecting water vapor. When water vapor condenses and forms water droplets, there is some heat release, called latent heat. The amount of water vapor in an air parcel is an exponential function of its temperature $($Clausius-Clapeyron relation$)$. Hence when a warm moist air parcel travels from the tropics to the poles and gets cold, the water vapor in it condenses and releases its 'latent' $($hidden$)$ heat.

Why would energy transport from the tropics to the poles increase with global warming?

The amount of water vapor in an air parcel is roughly an exponential function of its temperature, hence the small initial increase in temperature due to the greenhouse effect will increase the water vapor content in tropical air parcels, which get advected to the poles and release their latent heat.

Lapse rate feedback

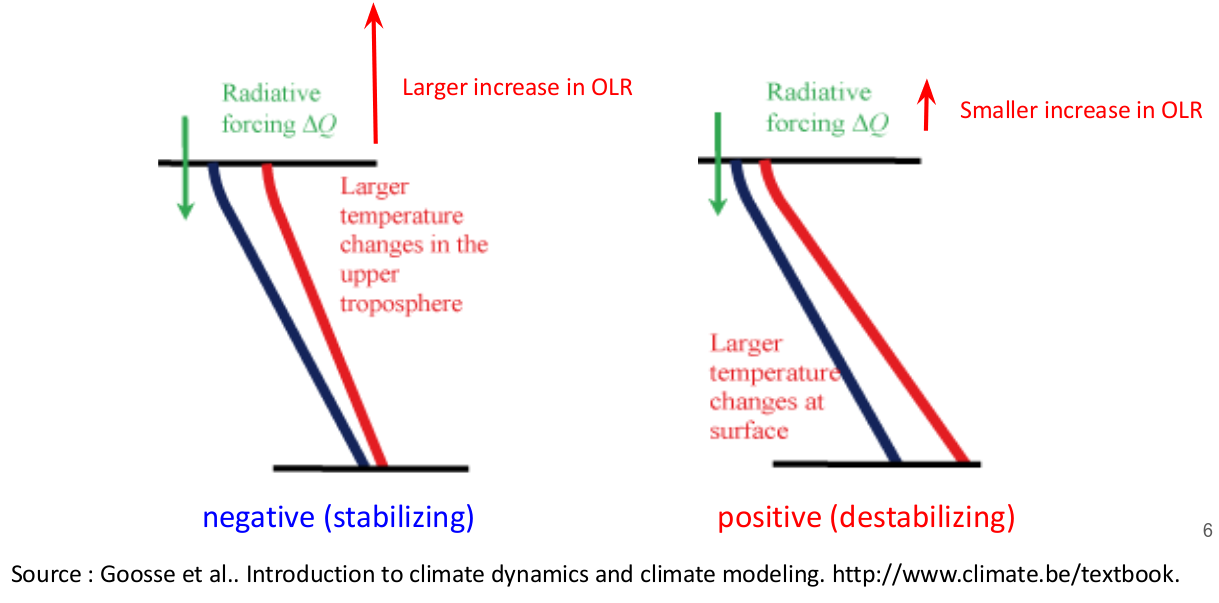

The lapse rate feedback refers to the vertical structure of temperature change.

The vertical temperature structure is illustrated in the figure above. In green is a radiative forcing such as an increase in greenhouse gases, which has the instantaneous effect of reducing the OLR. To balance this forcing, the surface and troposphere need to warm to increase the OLR. If the warming response is top-heavy, there is a larger increase in OLR, so less surface warming is needed to balance the TOA forcing. On the other hand, if the warming is bottom-heavy, there is a smaller increase in OLR, so more surface warming is needed to balance the TOA forcing.

Generally, as shown in the temperature change figures, the warming is top-heavy in the tropics and bottom-heavy in the Arctic. While the top-heavy warming structure in the tropics is well-understood, the reasons behind the bottom-heavy warming structure in the poles is a topic of research.

Conclusion

The commonly cited reason for polar amplification is the sea ice albedo feedback. However, other reasons such as an increase in atmospheric energy transport and the vertical structure of warming also seem to play a role. It is not yet clear what sets the vertical structure of warming in the Arctic, and how it interacts with the other feedbacks. In this whole discussion, we ignore the presence of clouds, which are important but hard to model precisely. We also ignore the seasonality of Arctic amplification, which is shown to be mainly a winter phenomenon.

Leave a Comment