Pint of Science talk : Understanding the Arctic amplification of global warming.

Published:

I gave a Pint of Science presentation on the 21st of May 2019 in Montreal. [This is written moreless as it was said, forgive the informal tone.]

I aimed to talk about the reasons why the Arctic is warming faster than the rest of the planet, and how we use simple climate models to get an understanding of the climate system. The beautiful NOAA satellite image was taken above the Arctic and demonstrates the complexity of the climate system. The presence of clouds, ocean, ice, land, vegetation all affect temperature, hence one way to approach climate science is to get an understanding of the system using simple models.

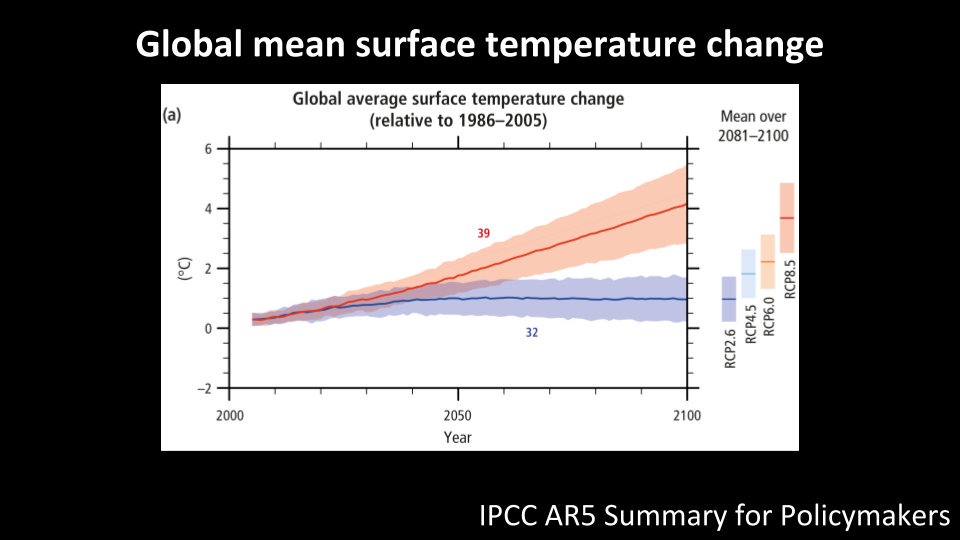

How much will the planet warm in the future? It depends on how much greenhouse gases the world emits and how sensitive the temperature is to increases in greenhouse gas concentrations. Two scenarios are shown above: one where we curb emissions and drawdown carbon, and limit the warming relative to 1986-2005 to 1 degree C by 2100; and the ‘business-as-usual’ scenario where we continue emitting high levels of greenhouse gases, in which case we will reach 4 degrees C increase by 2100.

We often talk about the warming in terms of global mean surface temperature change. But this warming has a pattern…

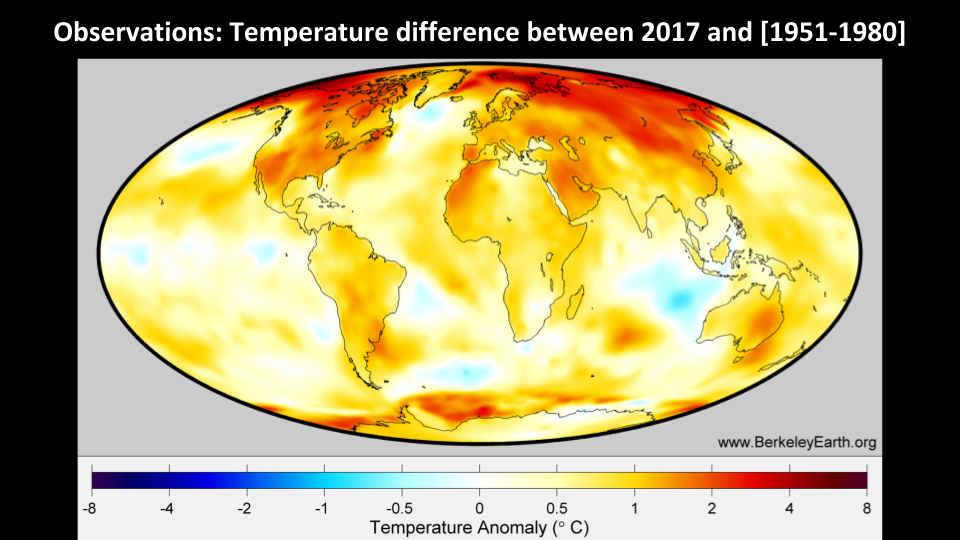

This map shows how much warmer 2017 was relative to the 1951-1980 period using observations. There are two main features : the land warms up faster than the ocean, and the Arctic is warming faster than the average.

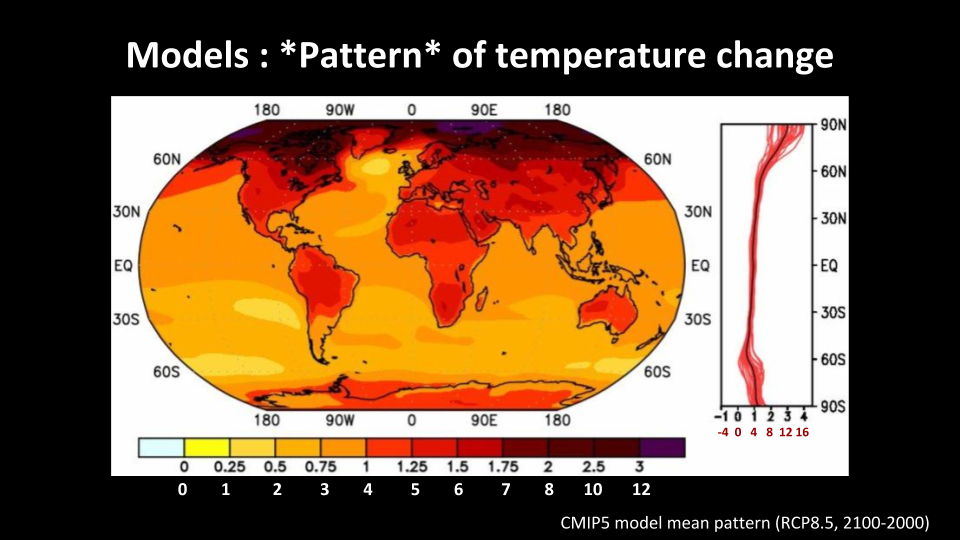

The climate models show the same thing. This is the pattern of temperature change from the state-of-the-art models: this is the temperature change between 2100 and 2000 assuming a ‘business-as-usual’ emissions scenario, and divided by the global mean surface temperature change. Supposing the global mean surface temperature change is 4 degrees C, then we can multiply everything by 4 to get the actual surface temperature change. Hence, we expect an 8 to 12 degrees increase in the Arctic by 2100 in a business-as-usual scenario.

My objective is to understand why the Arctic is warming faster using simple models.

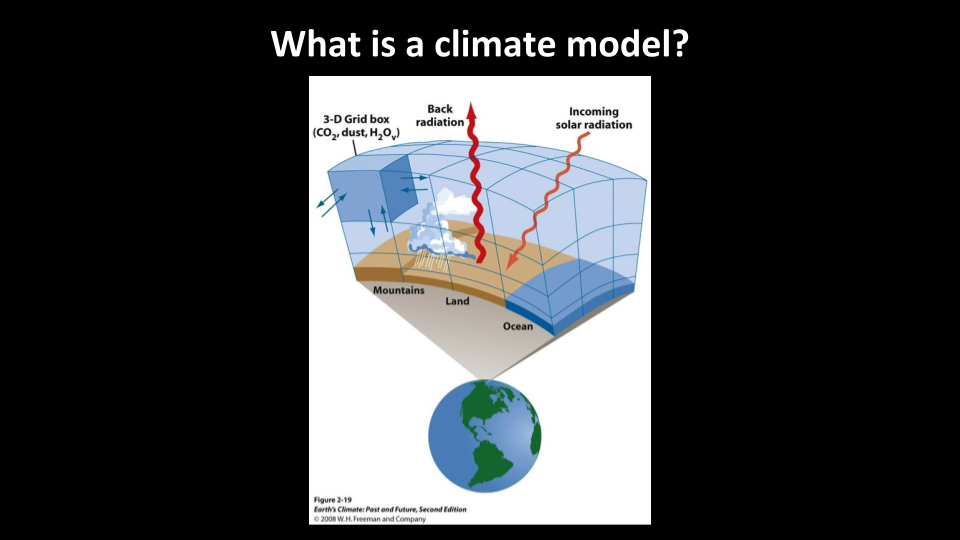

What is a climate model? We separate the atmosphere and oceans into boxes, and use equations for fluid motion $($air and water are fluids$)$ and energy transfer, and integrate them over time. Some processes, like cloud formation, happen on scales that are smaller than the size of the box. Hence, the models have a parametrization, which are approximations meant to simplify the model. The more precise the model is, the more processes it has to include. The IPCC models include a lot of processes: dust, vegetation, ocean biogeochemistry, etc. These all affect the temperature directly or indirectly.

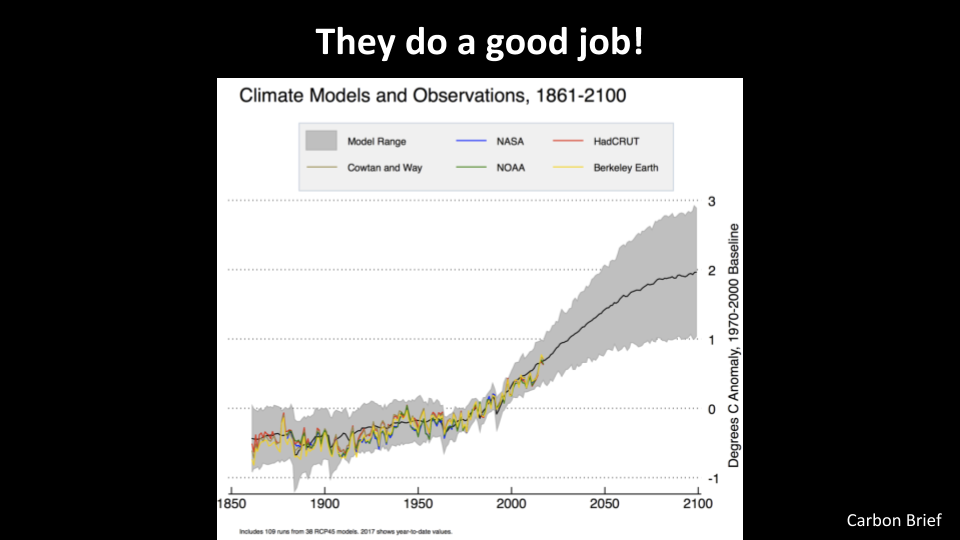

The IPCC models do a good job in simulating the climate system. The colored lines represent observations of the global mean surface temperature anomaly $($relative to 1970-2000$)$ from different organizations. The black line is the mean of 38 models, and in gray is the range of the models. The future predicted by these models is assuming a middle-of-the-road emission scenario $($RCP4.5$)$, which will get us to 2 degrees C increase by the end of the century.

The IPCC models do a good job when it comes to prediction, but they are hard to understand, as they include many processes. They also run on large supercomputers and take a long time to run.

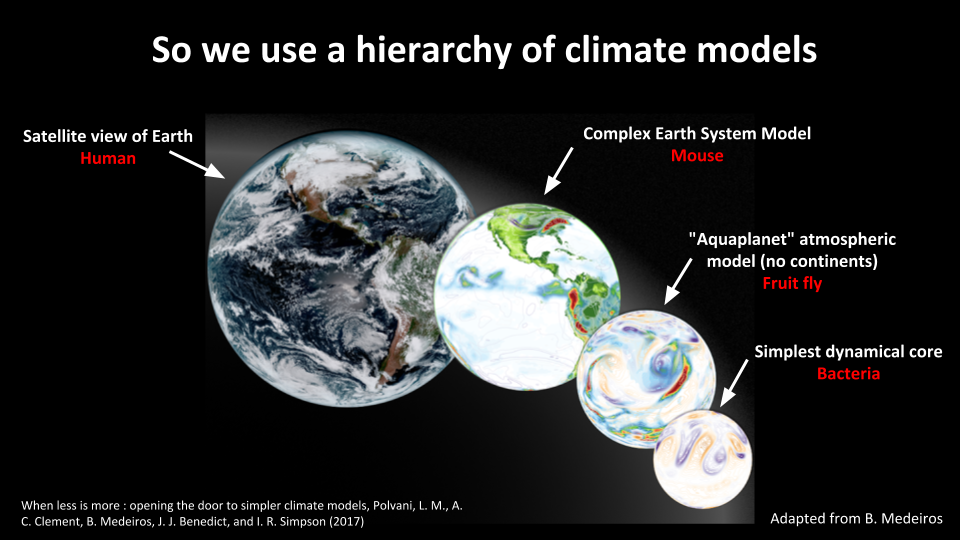

In order to overcome the problem of the complexity of the climate system, we use a hierarchy of climate models. The complex Earth system models are the ones used by the IPCC for prediction. If we want to focus on the atmosphere, we have “aquaplanet” models where we radically simplify the representation of the ocean, and get rid of all the continents. Finally, we can study just how fluid moves by using the simplest dynamical core. In reality, we adjust the complexity of the model used to the problem we are studying, so there are many more intermediate levels of complexity.

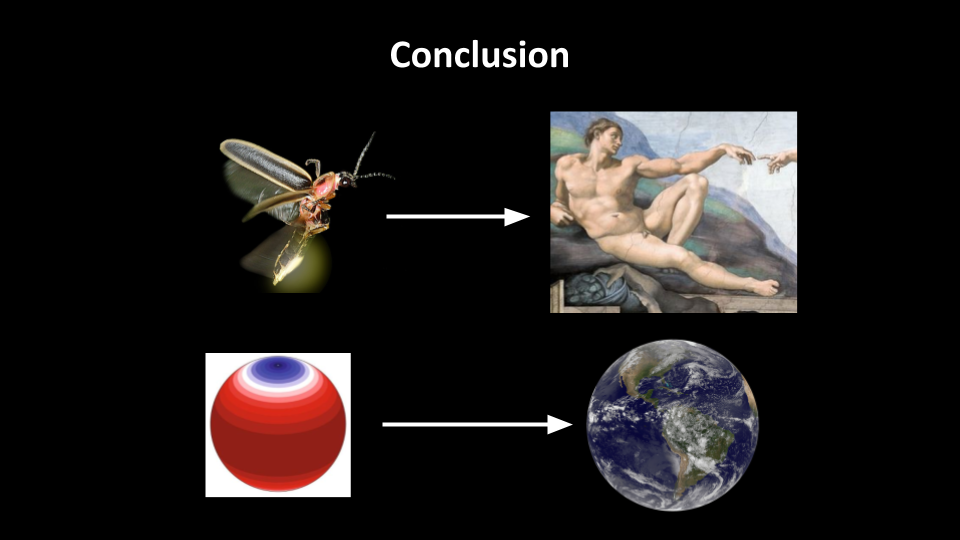

Much like a biologist would study mice, fruit flies and bacteria to get a better understanding of human biology, the idea is that studying these simpler models enables us to get a better understanding of the climate system.

What are the possible causes of Arctic amplification? How do we use simple models to understand them?

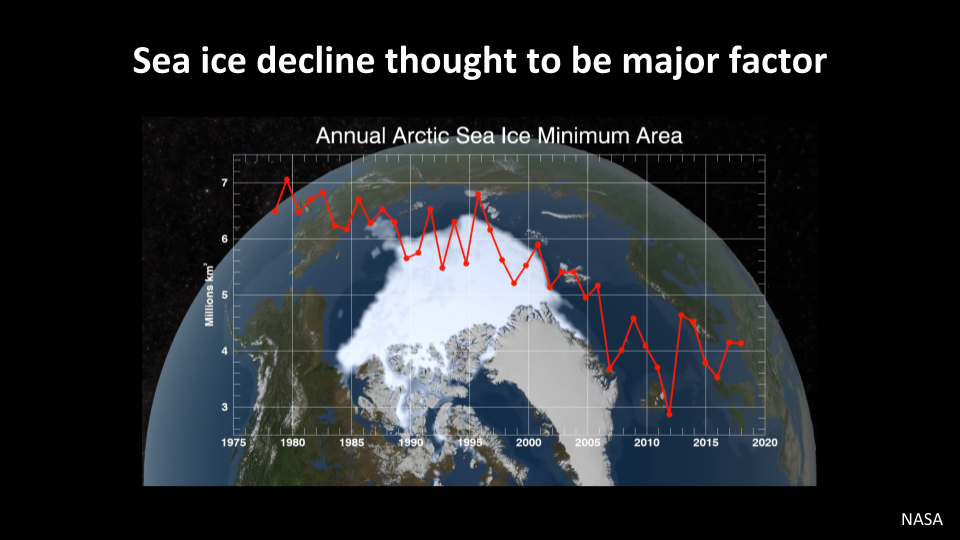

Sea ice is thought to be a major factor in the Arctic amplification of global warming. Here, the graph shows the minimum area of Arctic sea ice every year from the late 1970’s to now. There has been a ~50% decline in minimum sea ice area. When the highly reflective white sea ice is replaced by the dark ocean waters, additional radiation is being absorbed at the surface, leading to extra local warming.

On the other hand, if there are other processes that lead to a polar amplified temperature change, then the decline in sea ice might be a consequence of that rather than the driver of polar amplification.

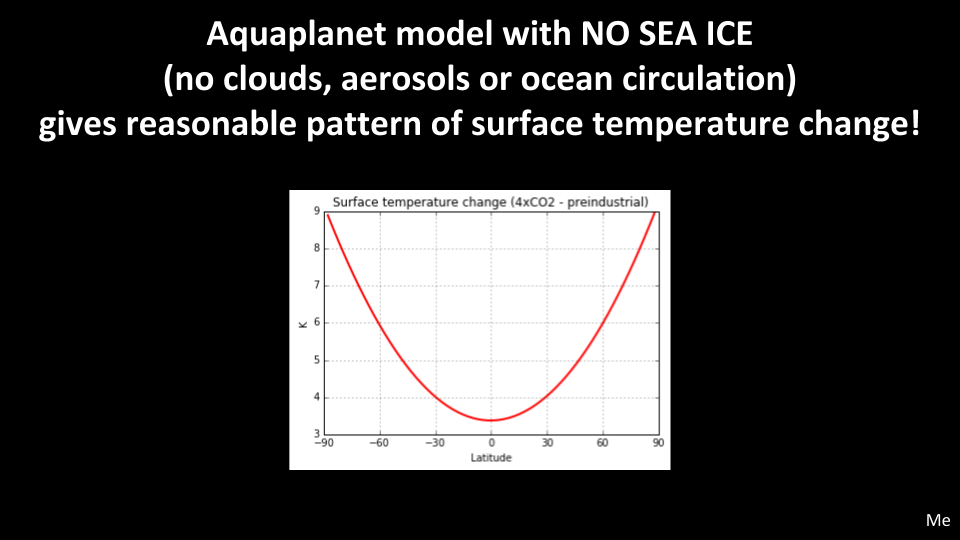

I ran a simple climate model, that has no continents $($aquaplanet$)$, no clouds, aerosols or ocean circulation, and NO SEA ICE. This is the surface temperature change pattern it has after a quadrupling of CO2 concentrations. This is reasonable since we expect the Arctic to warm 2-3x more than the global average.

What are the processes that lead to polar amplification in this simple model?

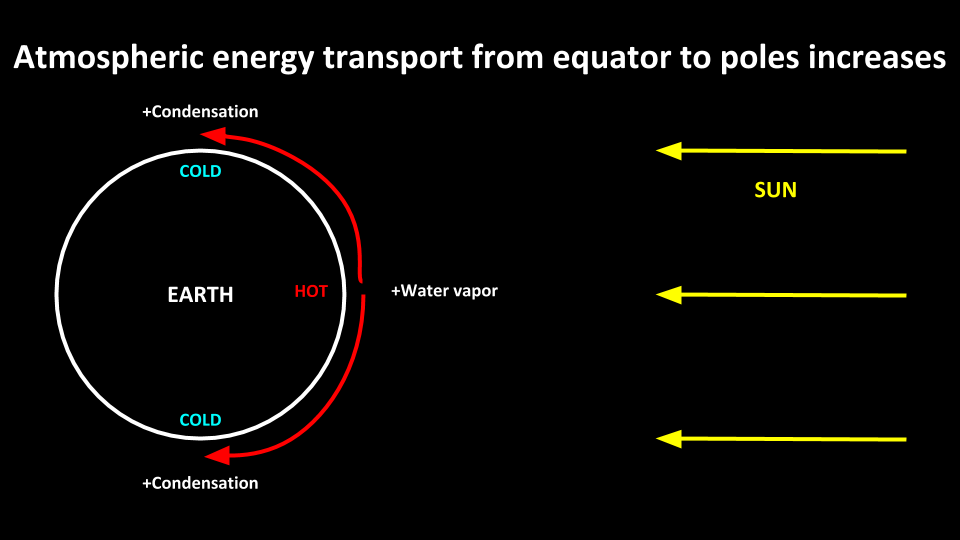

This is a very simple representation of solar radiation and the Earth’s surface. Since the angle between the solar radiation and the Earth’s surface is 90 degrees at the equator and 0 at the poles, the equator is hotter than the poles, and the polar atmosphere gets heated through atmospheric and oceanic energy transport. The warm air from the tropics gets transported to the poles, and keeps the difference in temperature between the equator and the poles relatively small.

With increasing greenhouse gases, we expect there to be more water vapor in the tropics, which gets transported to the poles, where it condenses and releases heat. Hence the amount of energy transport from the tropics to the poles should increase. That is one process that could lead to polar amplification in this model.

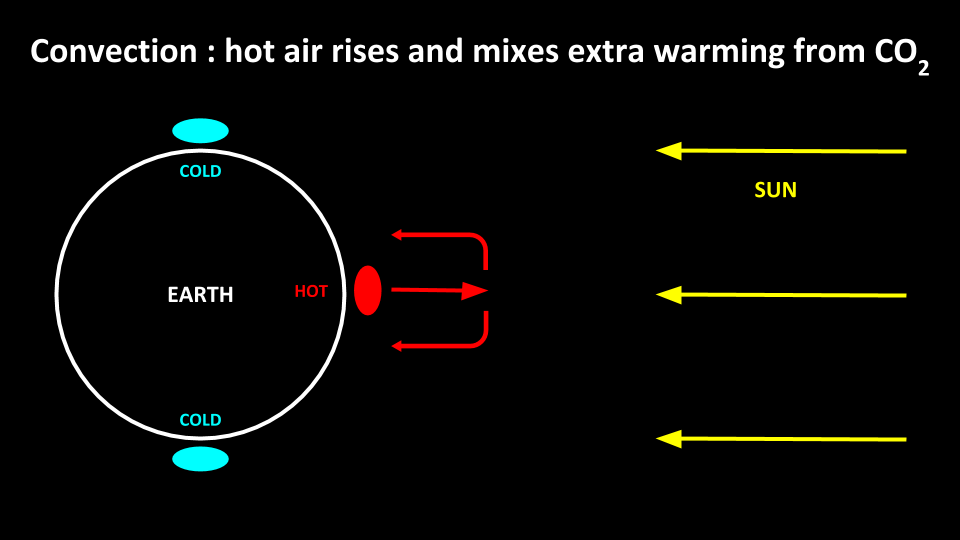

The other is convection: since the atmosphere in the tropics is heated from below, the hot air near the surface rises, and this leads to vertical mixing of the air. Hence, the extra warming from increasing greenhouse gases gets mixed vertically. In the poles, since there is no convection, the warming from increasing greenhouse gases stays near the surface.

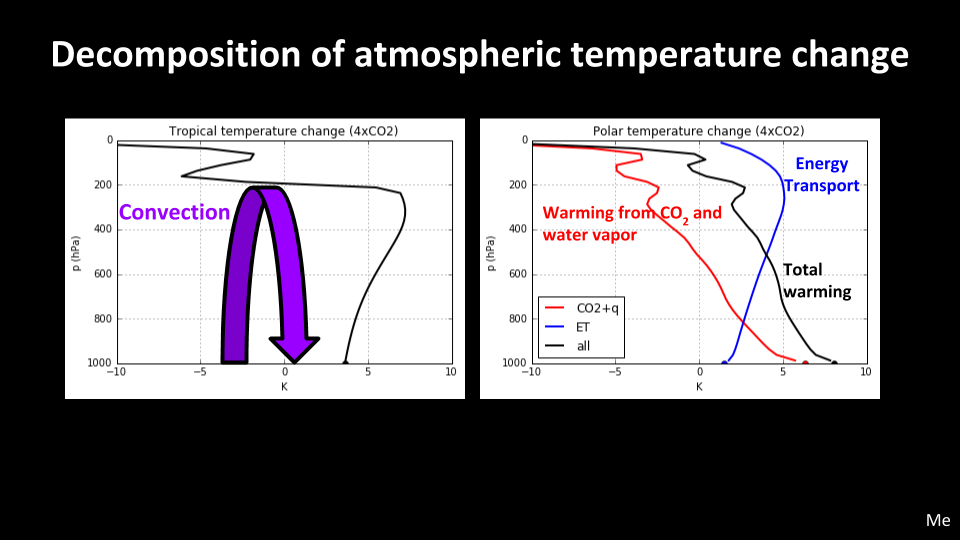

The advantage of using simple models is that we can do decompositions like this. This is the vertical structure of temperature change in the tropics and poles. In the tropics, since there is some vertical mixing, the warming is moreless vertically homogeneous. In the poles, however, the warming from increased CO2 and water vapor $($red$)$ is not mixed vertically, so it is bottom-heavy. And there is extra atmospheric energy transport $($blue$)$.

The takeaway message I would like to leave is the story of one approach of how we study a system as complex as the climate. We study simplified models of the climate to get a better understanding of the climate the same way biologists study smaller simpler organisms to get a better understanding of the human body.

Leave a Comment