Why does the Arctic warm more in winter than summer?

Published:

I am trying to understand how sea ice affects surface temperature in today’s climate and in projections of future climate change, and what drives the seasonality in Arctic temperature change.

Previous work on understanding seasonality of Arctic warming

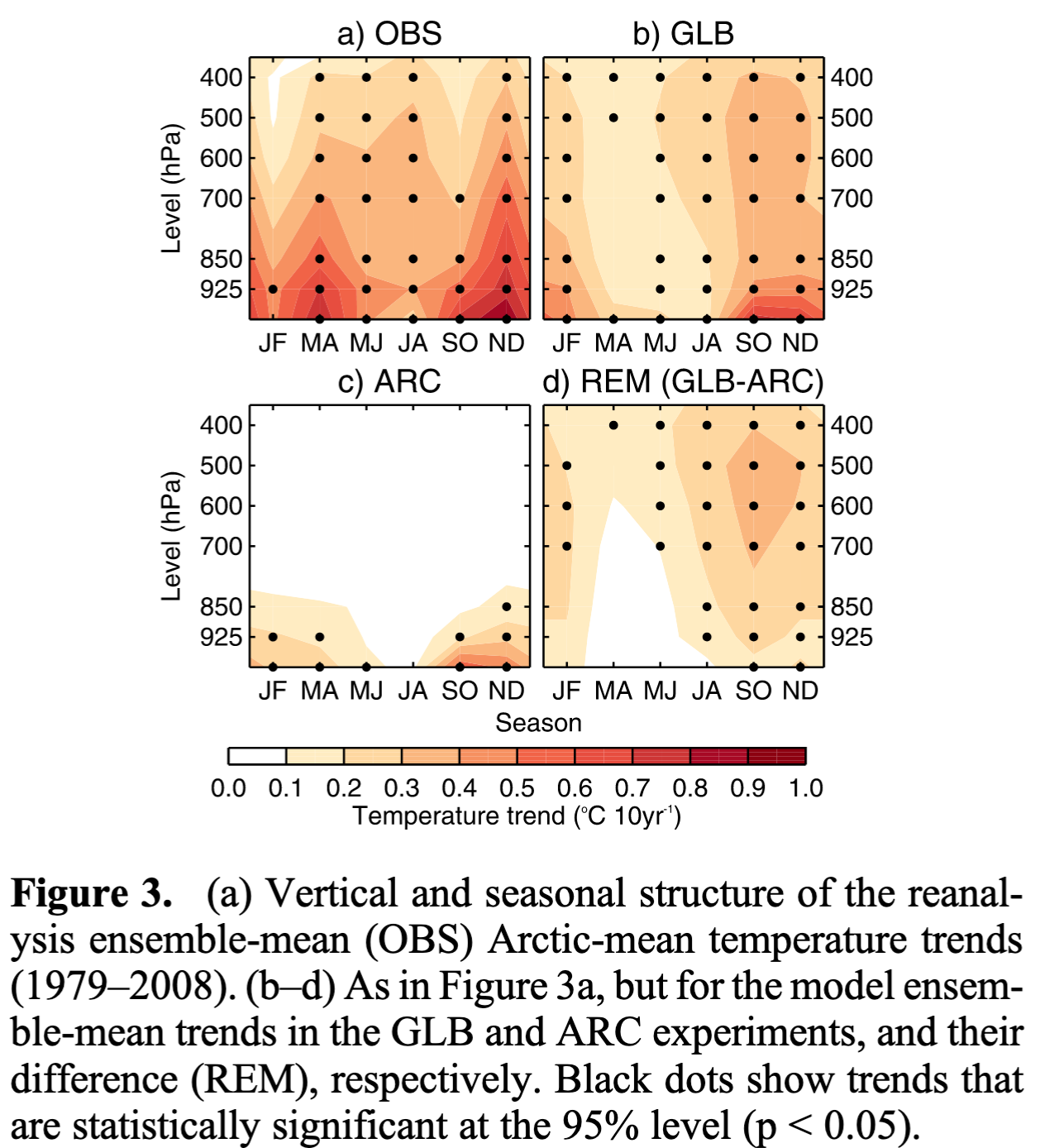

Panel (a) from the figure below from Screen et al. 2012 shows temperature trends over the 1979-2008 period averaged over the Arctic plotted over pressure levels (y-axis) and months (x-axis). While the mid- and upper-atmosphere warm throughout the year, the near-surface warms more in winter than summer.

Panel (b) shows trends from an atmospheric model where the sea surface temperatures (SSTs) and sea ice concentration (SIC) are prescribed to their observed evolution. Results are similar enough to observations. Panel (c) shows trends from an experiment where the SIC is prescribed to its observed evolution, the SSTs can respond in areas with sea ice change, and the SSTs are prescribed to the climatological annual cycle elsewhere. The seasonality in near-surface warming is reproduced in panel (c) where only the sea ice concentration (and SSTs where sea ice change occurs) are changed. This suggests that near-surface warming is correlated with the evolution of sea ice.

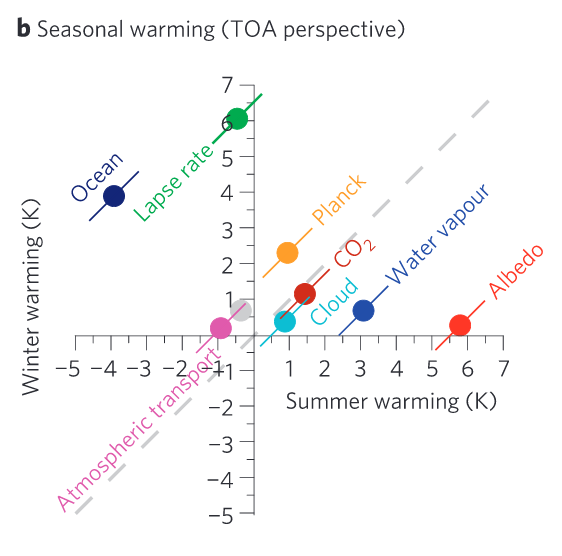

In this figure from Pithan and Mauritsen 2014, Arctic summer (x-axis) and winter (y-axis) surface temperature change are attributed to the various forcings and feedbacks from a top-of-atmosphere perspective. (See previous post on a follow-up to their work on the pattern of annual-mean warming.) The main driver of summer warming is the surface albedo feedback but it is counteracted by an increase in ocean heat uptake. The main drivers of winter warming are ocean heat release and a surface-enhanced lapse rate change.

The main mechanism seems to be that sea ice decline in summer leads to an increase in heat uptake by the ocean, which is then released in winter.

Eisenman simple sea ice model

I played with a simplification of a very simple sea ice model to better understand the thermodynamics of sea ice. This is taken from Eisenman’s sea ice work.

Eisenman’s model works by using the mixed layer enthalpy which evolves continuously from ocean to sea ice. The net surface flux $N$ $($in W/m$^2$, positive downwards$)$ dictates the change in mixed layer enthalpy $E$ $($in J/m$^2)$ : $\frac{\partial E}{\partial t} = N$.

Then, we can determine the surface temperature $T_S$ and the sea ice depth $h_{ice}$ depending on the sign of $E$:

- $E > 0$ : $T_S = \frac{E}{C_W} + 273$ and $h_{ice} = 0$

where $C_W$ is the mixed layer heat capacity. In this case, it is no different from a mixed layer of ocean water.

- $E < 0$ : $h_{ice} = -\frac{E}{L_f}$ and $T_S’$ such that $-\frac{k}{h_{ice}}(T_S’-273) = N$

where $T_S’$ is the dummy surface temperature, $L_f$ is the latent heat of fusion of sea ice, $-\frac{k}{h_{ice}}(T_S’-273)$ is the heat flux through the ice, and $k$ is ice thermal conductivity.

Then, if $T_S’<273K$, $T_S=T_S’$ and if $T_S’>273K$, $T_S=273K$ and sea ice melts with $\frac{\partial h_{ice}}{\partial t} = -N/L_f$.

My toy experiments

To simplify the model as much as possible and isolate the effects of the thermodynamics of sea ice, the latent and sensible heat fluxes are ignored, I assume a seasonally constant downwelling longwave radiation, and I assume that the longwave emission depends linearly on surface temperature:

$\frac{\partial E}{\partial t}(t) = SW_{down}(t) + LW_{down} - A - B T_S(t)$

where $SW_{down}(t)$ is prescribed from GCM values averaged poleward of 70 degrees North. And, $A + B T_S$ is a linearization of $\sigma T_S^4$.

Relaxing the assumptions described above does not meaningfully affect the results below.

However, this kind of surface energy budget integration only provides a limited insight, as $LW_{down}$ and the turbulent surface fluxes would change as a function of $T_S$ in a full GCM simulation.

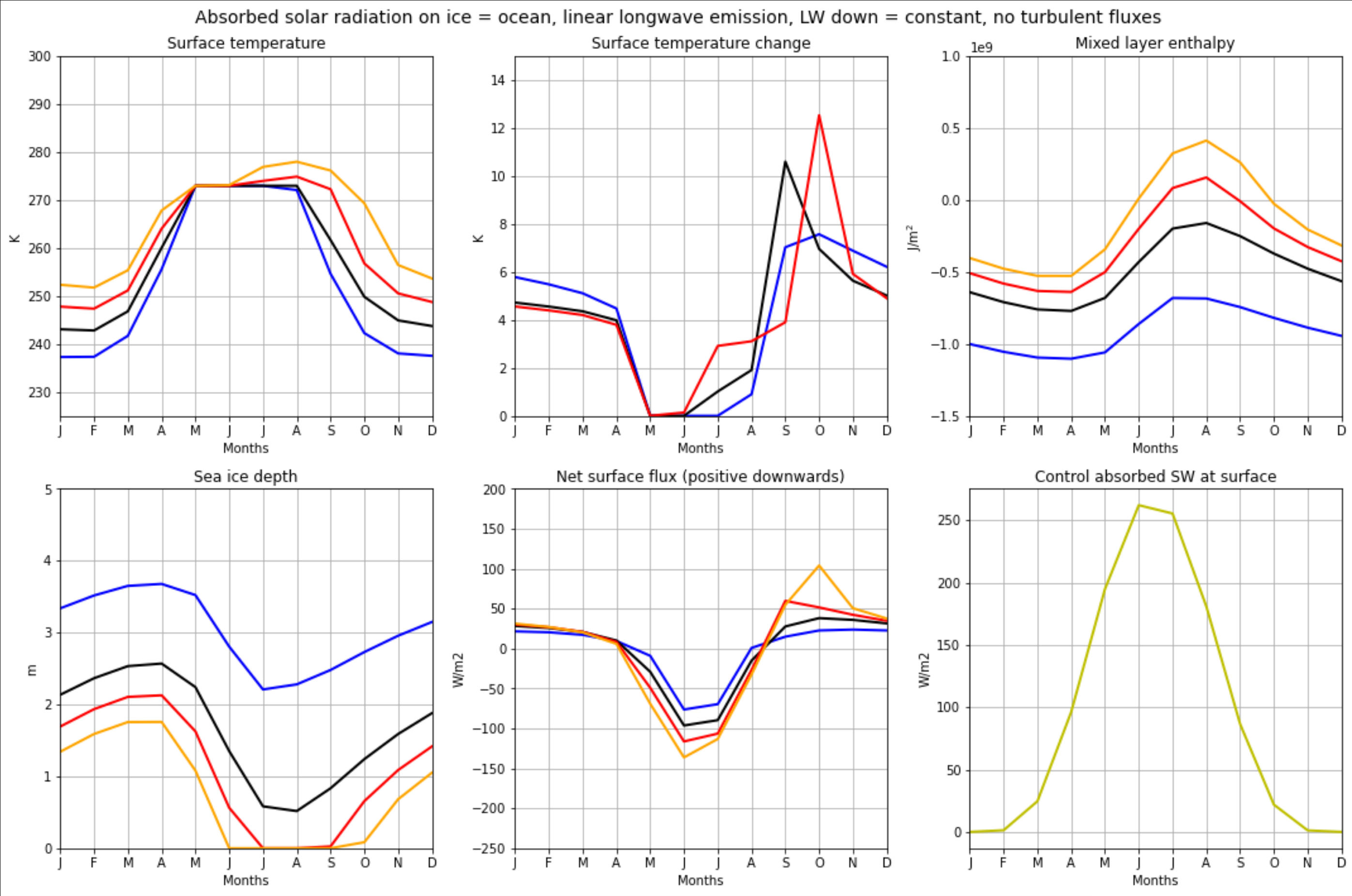

The figure above shows values for the surface temperature, surface temperature change, mixed layer enthalpy, sea ice depth, net surface flux ($N$), and $SW_{down}(t)$ for different values of $LW_{down}$.

It seems like the surface temperature is particularly stable at 273K, as the extra energy goes into melting the sea ice (hence reducing $h_{ice}$) instead of increasing the temperature, as described in the algorithm above. The seasonal cycle of surface temperature change is then similar to the observations. Obviously, there is a lot more going on in the real world, but I wonder what the contribution of this effect is to the seasonal cycle of Arctic surface temperature change.

In a world with no sea ice

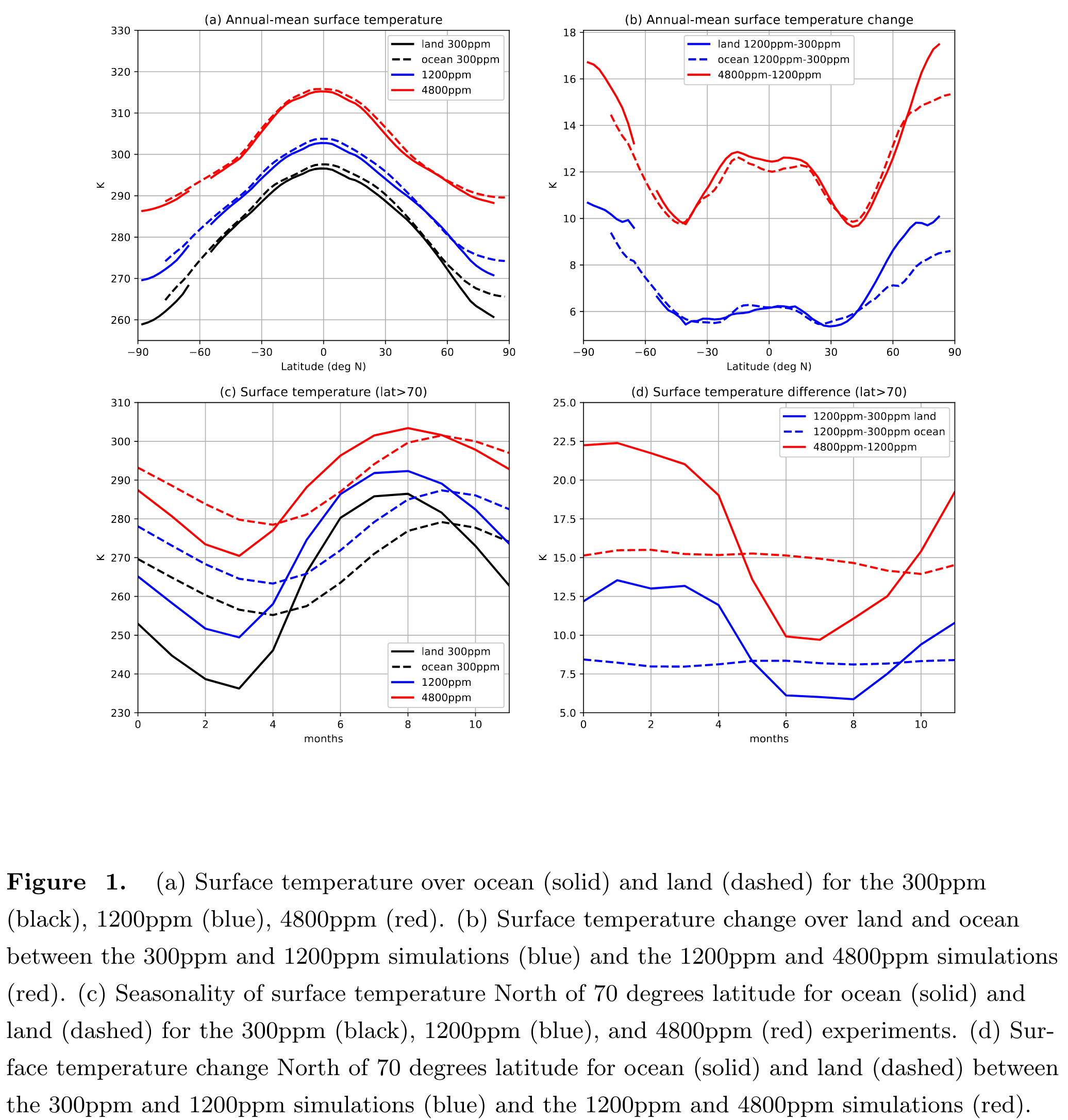

I ran some idealized GCM simulations with no sea ice or clouds using Isca. Continents differ from ocean only by their mixed layer depth, which is 10 times smaller than that of the ocean. I explore the pattern and seasonality of surface temperature change by running three simulations: 300ppm, 1200ppm, and 4800ppm.

Panel (d) below shows the surface temperature change averaged poleward of 70 degrees North for land (solid lines) and ocean (dashed lines). While the ocean warms by the same amount year-round, land warms more when it’s the colder (see panel (c)). (The months should be shifted.)

There are more details to come in a future pre-print. But, in a nutshell, this difference in seasonality of high latitude warming is explained by the smaller surface heat capacity of land (which leads to a larger seasonal cycle in temperature) and the nonlinearity of the temperature dependence of surface longwave emission, $\sigma T_S^4$ (which forces cold temperatures to warm more to reach the same increase in emission). We also explore the seasonality of high latitude lapse rate changes in these simulations and the role of advection in smoothing out expected differences in near-surface atmospheric temperatures over land and ocean.

Conclusion

Sea ice undoubtedly plays a dominant role in the seasonality of Arctic surface temperature change. In simulations with no sea ice, the ocean warms by the same amount year-round. The main mechanism in comprehensive climate models seems to be an increase in ocean heat uptake in summer as the sea ice melts, which leads to increased ocean heat release in winter.

I played with a toy sea ice model, which suggests that the sea ice surface temperature is quite stable at the melting temperature as the extra energy received goes into melting the sea ice instead of increasing the sea ice surface temperature.

And, in a world without sea ice, the high latitude continents warm more in winter than summer due to their small surface heat capacity and the nonlinearity of the temperature dependence of surface longwave emission.

I would like to add a simple sea ice module to Isca to better understand how it interacts with the other components of the climate system.

Leave a Comment